Patel, A; Chen, Z. Yang, Z; Gutierrez, O.; Liu, H.-W.; Houk, K. N.; Singleton, D. A. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2016,138, 3631-3634

Contributed by Steven Bacharach

Reposted from Computational Organic Chemistry with permission

'

'

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Contributed by Steven Bacharach

Reposted from Computational Organic Chemistry with permission

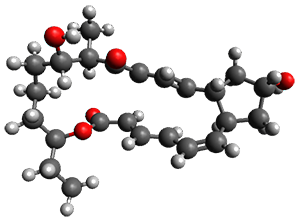

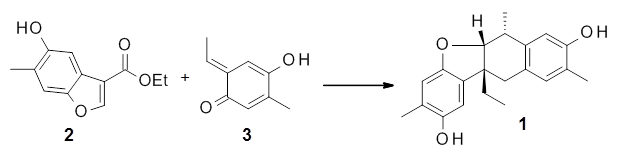

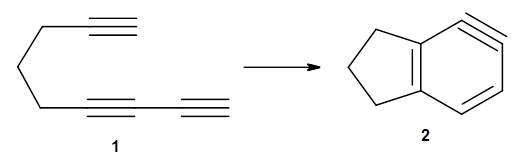

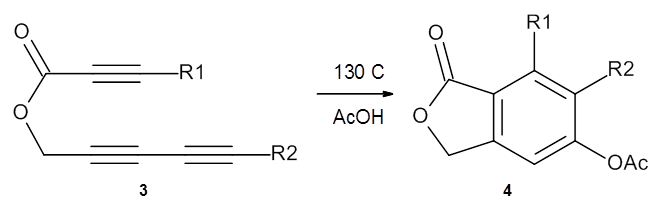

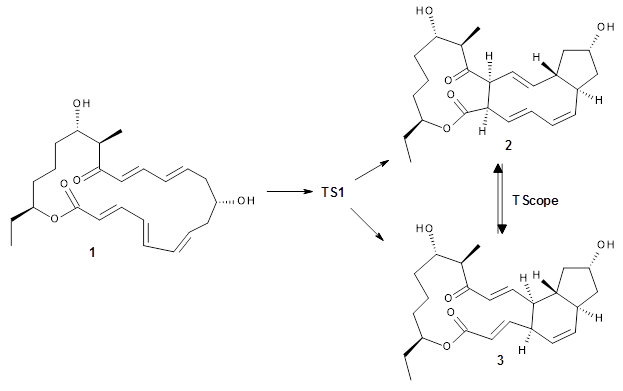

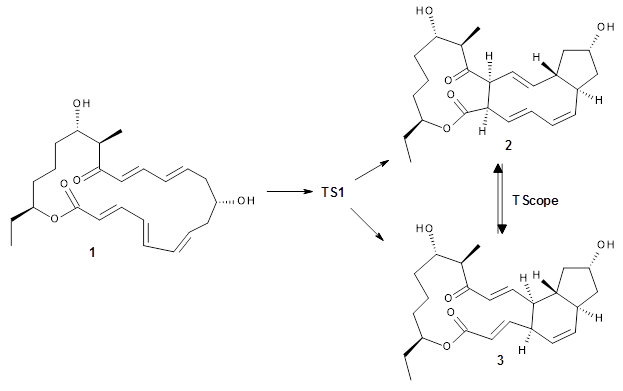

Enzyme SpnF is implicated in catalyzing the putative [4+2] cycloaddition taking 1 into 3. Houk, Singleton and co-workers have now examined the mechanism of this transformation in aqueous solution but without the enzyme.1 As might be expected, this mechanism is not straightforward.

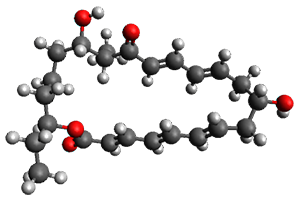

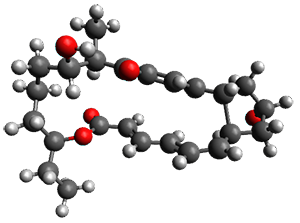

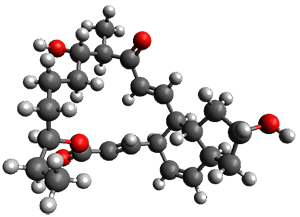

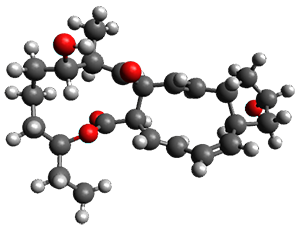

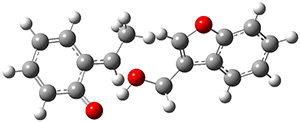

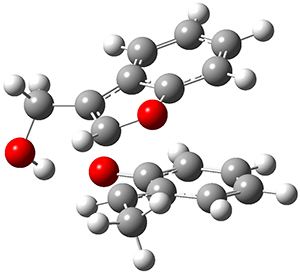

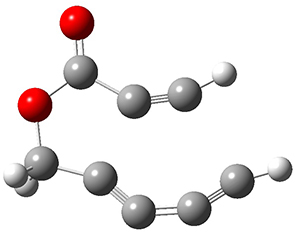

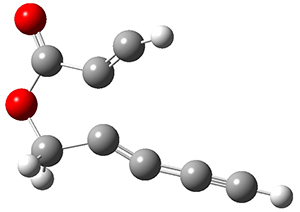

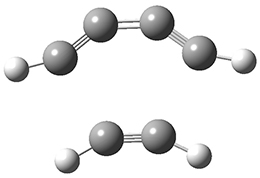

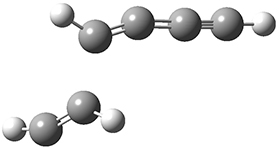

Reactant 1, transition states, and products 2 and 3 were optimized at SMD(H2O)/M06-2X/def2-TZVPP//B3LYP-D3(BJ)//6-31+G(d,p). Geometries and relative energies are shown in Figure 1. The reaction1 → 2 is a formal [6+4] cycloaddition, and the reaction 1 → 3 is a formal [4+2] cycloaddition. Interestingly, only a single transition state could be located TS1. It is a bispericyclic TS (see Chapter 4 of my book), where these two pericyclic reaction sort of merge together. After TS1 is traversed the potential energy surface bifurcates, leading to 2 or 3. This is yet again an example of a single TS leading to two different products. (See the many posts I have written on this topic.) The barrier height is 27.6 kcal mol-1, with 2 lying 13.1 kcal mol-1 above 3. However, the steepest descent pathway from TS1 leads to 2. There is a second transition state TScope that describes a Cope rearrangement between 2 and 3. Using the more traditional TS theory description, 1 undergoes a [6+4] cycloaddition to form 2 which then crosses a lower barrier (TScope) to form the thermodynamically favored 3, which is the product observed in the enzymatically catalyzed reaction.

1 (0.0)

| |

TS1 (27.6)

| |

2 (4.0)

|

3 (-9.1)

|

(24.7)

| |

Figure 1. B3LYP-D3(BJ)//6-31+G(d,p) optimized geometries and relative energies in kcal mol-1.

Molecular dynamics computations were performed on this system by tracking trajectories starting in the neighborhood of TS1 on a B3LYP-D2/6-31G(d) PES. The results are that 63% of the trajectories end at 2, 25% end at 3, and 12% recross back to reactant 1, suggesting an initial formation ratio for 2:3 of 2.5:1. The reactions are very slow to cross through the “transition zone”, typically 2-3 times longer than for a usual Diels-Alder reaction (see this post).

Once again, we see an example of dynamic effects dictating a reaction mechanism. The authors pose a tantalizing question: Can an enzyme control the outcome of an ambimodal reaction by altering the energy surface such that the steepest downhill path from the transition state leads to the “desired” product(s)? The answer to this question awaits further study.

References

(1) Patel, A; Chen, Z. Yang, Z; Gutierrez, O.; Liu, H.-W.; Houk, K. N.; Singleton, D. A. “Dynamically

Complex [6+4] and [4+2] Cycloadditions in the Biosynthesis of Spinosyn A,” J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2016,138, 3631-3634, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b00017.

Complex [6+4] and [4+2] Cycloadditions in the Biosynthesis of Spinosyn A,” J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2016,138, 3631-3634, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b00017.

InChIs

1: InChI=1S/C24H34O5/c1-3-21-15-12-17-23(27)19(2)22(26)16-10-7-9-14-20(25)13-8-5-4-6-11-18-24(28)29-21/h4-11,16,18-21,23,25,27H,3,12-15,17H2,1-2H3/b6-4+,8-5+,9-7+,16-10+,18-11+/t19-,20+,21-,23-/m0/s1

InChIKey=JEKALMRMHDPSQK-ZTRRSECRSA-N

InChIKey=JEKALMRMHDPSQK-ZTRRSECRSA-N

2: InChI=1S/C24H34O5/c1-3-19-8-6-10-22(26)15(2)23(27)20-12-11-17-14-18(25)13-16(17)7-4-5-9-21(20)24(28)29-19/h4-5,7,9,11-12,15-22,25-26H,3,6,8,10,13-14H2,1-2H3/b7-4-,9-5+,12-11+/t15-,16-,17-,18-,19+,20+,21-,22+/m1/s1

InChIKey=AVLPWIGYFVTVTB-PTACFXJJSA-N

InChIKey=AVLPWIGYFVTVTB-PTACFXJJSA-N

3: InChI=1S/C24H34O5/c1-3-19-5-4-6-22(26)15(2)23(27)11-10-20-16(9-12-24(28)29-19)7-8-17-13-18(25)14-21(17)20/h7-12,15-22,25-26H,3-6,13-14H2,1-2H3/b11-10+,12-9+/t15-,16+,17-,18-,19+,20-,21-,22+/m1/s1

InChIKey=BINMOURRBYQUKD-MBPIVLONSA-N

InChIKey=BINMOURRBYQUKD-MBPIVLONSA-N

'

'This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.